- Home

- Oskar Jensen

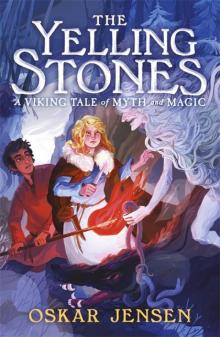

The Yelling Stones

The Yelling Stones Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Important People

Some Words

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

Oskar Jensen

Copyright

For Nils Jensen

IMPORTANT PEOPLE

SOME WORDS

‘In the long-before – the bad old days when men wore hair all over, nothing more, and spirits stalked about, and all men saw – this land was given over to the bear, the wolf, the boar. There lived three sisters in those days, one large, one squat, one thin; and whether they were troll or witch, or both, no one knew, but it’s certain that they kept their own company, and were seen only at night.

‘That was for the best, for they wore their hair long to their toes. Thick and matted it was too, with flies and worse things in, and never cut, so all you could see were the ends of their lumpen noses, and sometimes, a dark eye.

‘Well, one midwinter’s night, they crept from the woods to a sacred place – it fairly reeked of power – and there they formed a circle, and began to make a spell. And such a spell it was: a hex to crack this land apart and lay it at their taloned, warty feet. And as they worked it, they sucked the strength from the earth below and the trees around, so that they smiled wickedly behind their hair. Soon enough, all that power felt that good, that they just had to yell for the joy of it. A little more, and the world would be theirs.

‘But all that magic must have made them a touch slow, for they lost their heads for time, and right before the work was done, the weakling winter sun arose and turned them into stones. One large, one squat, one thin: the Yelling Stones, frozen fast, and the yell itself – a mad, terrible, powerful thing – hanging in the air between them. Hanging forever on the edge of glory.’

ONE

Denmark, 958 AD

It was the first day of spring. The Yelling Stones, snow-swaddled, loomed before the great hall that bore their name and waited for something to happen. It would not take long. A short ride south-west, Astrid Gormsdottir was shouting to the sky.

‘Stay your hand, dark power, for I am queen of the spring, and I forbid night to fall without my leave!’

‘Oh, how can you say such things, Astrid? And as if you could have a midsummer night with snow still lying. Why, there’s no more difference between the first day of spring and the last day of winter, than between … than between …’

‘You know what, Bekkhild, I’m going to keep riding until you can think of a decent end to that sentence. I’ll probably have to go on into tomorrow morning,’ said Astrid.

And with that, Astrid spurred her horse away from her companion, and the little group of servants following behind.

‘Astrid,’ shouted Bekkhild, ‘do come back! It’ll be dark soon. You’re sure to get lost, and the king will be furious.’ But Astrid never heard: the words were lost on the wind.

She was a young girl, tall, slender, and well wrapped up against the cold, with fur at her shoulders and a fur cap above, her thick gold plait streaming out behind as she urged her mount down the slope, towards the trees.

‘Come on, Hestur,’ said Astrid, to her snow-white horse. ‘If you’re just a little faster, we can leave them behind, and then we’ll be alone – at last! We’ll trot towards the gorge, follow the river round, and come up behind the hall, hidden in the forest the whole time.’

She pulled one glove off with her teeth to stroke Hestur’s mane and neck. Coarse hair and hard muscles strong beneath her fingers. Bending low, she murmured in his ear. ‘Then I’ll give you a fine gallop over the plain to Jelling, and I bet we beat them back as well!’

The horse snorted, and bucked its way downhill, where the snow lay less thick beneath the spreading branches, the first green shoots peeping through the white. Astrid whooped, urging him on.

Bekkhild sighed, and pointed her mare down the hill. ‘Urgh, that Astrid!’ she said. ‘Why is it always me that has to watch her …?’

Astrid had never felt more free. Air stung her cheeks. Her thighs smarted from lack of practice. It was all so … so alive. ‘As if I’m going to spend my first day outside plodding along with Bekkhild the boring, after months cooped up in the hall, when we could go anywhere! Just you and me, Hestur: you and me and the whole of the North to ride in!’

On and on, and soon the cries, and the soft thudding of snow-muffled hoofs, died away behind them. Girl and horse rode alone between tall oaks, ash and beeches. Astrid loved the trees. Their tall trunks, rank upon rank, could be a guard of honour. She sat a little straighter in the saddle, small chin and snub nose tilted up to acknowledge her loyal tree-followers.

But once the first thrill of solitude was passed, she came back to herself, and frowned. ‘I wish you’d go a bit faster, Hestur,’ she said. ‘It’s not half so light as it was, and we should have hit the river long ago …’

She broke off as a rushing sound grew louder, and soon the sight she expected lay before them: the ground falling away to their right, tumbling down a high gorge to churning water, made thick by melting snows. White willows bent their heads, and trailed slender fingers in the stream.

Astrid smiled and nudged Hestur left along the valley, but it was a thin smile: the shadows were longer now, pooling to a general darkness.

That was when she heard the first howl.

Instantly Hestur’s ears were up and his nostrils flared. Astrid too was bolt upright and tense, but she forced herself to lay a hand on the horse’s neck and whisper. ‘There now, boy, one wolf’s no worry for the likes of us. But it’s time to be getting home. Come on … Come on, Hestur!’ For his legs were rooted in the snow and he would not heed her, even when she dug in her heels. And now his ears lay flat, ready for the danger.

Cross with the horse and with herself for losing track of time, Astrid tried to think of what to do next. But all she could think of were hard yellow eyes, sharp teeth, and all the times when she’d been little, and cried at the dark.

Another howl, deeper than the first, came from somewhere in front of them. It was answered away to their left, and then again, behind, louder still. Or, was that two howls together?

Astrid was fumbling at her waist for her long knife when it happened. A snarling at their left and Hestur bolted, twisting to the right, lurching down the sheer falls of rock towards the river. He was spooked, hoofs skittering on the soft edge of the gorge. Loose stones tumbled into darkness and Astrid clung to his neck, every bit as terrified, certain they would fall.

If she squeezed shut her eyes and only held on,

everything might still be all right.

And then – thank the gods – they were down, and going slowly, and she could raise her head and open her eyes.

A wolf was looking back at her.

Astrid choked back a scream. You’re enormous, she thought, but she couldn’t be sure. He was black enough to be little more than a burning pair of eyes in the night – it was definitely night-time now – and near enough that he might spring.

Just then she felt a lapping at her feet and almost jumped out of the saddle, before realising that Hestur had backed into the river itself. The dark water ran around her ankles, deathly cold.

The big wolf sank back on its haunches and opened its jaws. The howling was all around them, on both banks, a whole pack, emboldened by the long lean winter and their gnawing white hunger. The brute in front of her arched its back, winding up like a horrid hairy coil.

Astrid drew her knife. I’m just a girl, she thought. The wolf sprang.

Then it was bright hot and the red flame all around. Smoke stung her eyes and made her head swim, so she thought she saw a boy, brandishing fire in each hand, the wolves shrinking from the burning torches.

‘Away, troll-steeds! You, Gauti’s hound, and you, sun-swallower! Slink off the lot of you, harm-crew of the forest; lope off and slake your blood-thirst at some other feast!’

‘What the Hel?!’ said Astrid. For there was a boy, and now he turned, his head wreathed by the flames. The wolves were gone. Hestur surged onto the bank, towards their rescuer. The boy smiled – a nice smile, she thought.

And then he fell to the ground, and started screaming.

Then there were voices, people, dogs and horses: Bekkhild; Odd and Bredi – the thralls who had ridden out behind them – and someone had taken up Hestur’s reins from where they hung, neglected.

‘Wolves?’ someone was asking, and, ‘Are you hurt?’

And there was Bekkhild, saying, ‘And what’s wrong with him?’

Astrid shook her head clear. She saw the boy spreadeagled on his back, thrashing his limbs, half in and half out of the water. Whether that was foam on his lips, or spray from the river, was hard to tell in so little light.

‘And who is he?’

‘He’s in a trance!’

‘You’d think a trance would be quieter …’

His whole body shook as if worried by a dog, and he was roaring loud enough to shame the wolves. Astrid blinked, shrugged her shoulders, pulled herself together. Time to act like her father’s daughter.

‘That’s the boy who rescued me,’ she said. ‘Lay him across your horse, Bredi; you can share with Odd. We shall take him back to Jelling.’

TWO

The news arrived before them, for Astrid, still shaken, kept pace with the witless boy, and Bekkhild and the others rushed ahead, eager for warmth, shelter and attention. The grubby faces of the grooms were lit with curiosity as they handed Astrid lightly down, and hauled the boy off Bredi’s horse with rather less grace. ‘Bring him,’ she said to the thralls, and strode into the hall of Gorm the Old.

‘Was it wolves then, Astrid?’

‘You silly girl!’

‘Have you captured an elf on your ride, child?’

The evening’s feasting had begun, and a hundred insolent revellers crowded in on her, closing out the fresh spring air with their faces, their questions, and their bad breath. Chin up, Astrid ignored the voices that came at her from either side, as she walked between the central fires and the long earth banks against the walls that served as benches. She hoped that anyone who saw her red cheeks in the dim light, flushed with embarrassment, would put it down to the coldness of the night and the heat of the hall. But oh, how she hated returning to that crammed, heaving hall; the dark, stinking, smoky prison of her every winter.

They wouldn’t dare address me like that if I were a boy, she thought, and then, I am so very, very hungry. Out loud, she muttered a tetchy ‘Hurry up,’ to Odd and Bredi, who were carrying the boy.

The hall was long: there was none so large in all the North lands. Sweat dripped from red faces, and in dark corners, dogs worried discarded gristle. Somewhere above, between dark rafters, scuttled little spirits that you never saw – tiny guardians of the hall, who slunk down at night to finish the food and sip the dregs from the drinking-horns. People, dogs, spirits: the place was so crowded …

Astrid’s lungs were itching from the fumes and her slim legs were trembling, but at last she was nearing the end. Before her loomed the dais, a platform the width of the hall, floored with oak planks rather than beaten earth, and there, beyond the high table – hard to see for all the smoke, fragrant with the scent of juniper and spruce, and for the shadows that crept from dark corners – there on a craggy throne of greying ash – his silvered beard sweeping the tabletop – there was her father.

Astrid looked up, and though all eyes were on her she was aware only of his: grey, watery, failing, yet still the eyes of a king.

But it was not King Gorm who spoke first. A voice cut in from Astrid’s right – ‘I hear someone got lost playing in the woods.’

She glared, stung out of her silence. ‘I was not lost,’ she said. ‘The wolves had come right up, this side of the gorge. They’ve never done that before.’

‘And of course you’re old enough to say “never”,’ replied the voice. It was dry, amused, dusty: the speaker was her brother, Haralt. Tall and gaunt, he had their father’s long nose, but as yet, only a straggly blond excuse for a beard. At twenty, he was just six years her elder, and Astrid was on the point of a still angrier reply, when a rumbling cough, like distant thunder, came from the depths of the silver beard before her. King Gorm was ready to speak.

‘Dumb brutes would never come so close. When wolves lose their fear like this, there’s sure to be a witch-rider at the back of it, spurring them on. That’s the problem with living by the Yelling Stones – you get all sorts of creatures, drawn to their power.’

‘Really, Father,’ replied Haralt, ‘I wish you’d drop this notion that witches ride wolves like we ride horses. I’ve certainly never seen such a thing.’

‘Small wonder,’ another voice broke in, now from Astrid’s left. This one was low, almost a growl: Knut, her eldest brother, sat at the king’s right hand. He looked like he sounded: big, brown and shaggy. Gold glinted on his massive upper arms.

‘How would you ever see a witch-rider, brother,’ Knut went on, ‘when you’ve never seen fit to come on a wolf hunt! Speaking of which, I may as well take a gang out tomorrow. The men could use a good hunt after sleeping through the winter. Why don’t you come along, Haralt, and see if you can bag the witch yourself?’

‘Some of us have more important things to do than running round the woods, chasing stories,’ said Haralt. ‘And I’ll add this, Knut: if you do think you spot a witch, then ask yourself how many horns of ale you’ve drunk that day before telling any tall tales.’

Astrid sighed. This was shaping up into a typical row – the brothers had never got on. Usually at this point, she shut up and pretended not to exist. It always worked; everyone else somehow seemed to be pretending the same thing. But not this time. She owed it to her rescuer to seize the king’s attention.

‘Father,’ she said, raising her voice above Knut’s next words, ‘I have brought the boy who saved me. He deserves much honour … but … but something has happened to him …’

‘Bring him forward. Let’s see this saviour of yours.’ Again, it was not the king who spoke, but the last of the four who were sat on the dais, this time immediately at the king’s left. Queen Thyre.

‘Here he is, Mother,’ said Astrid, and motioned the thralls forward with their burden. The hall was silent now, so quiet that Astrid imagined she could hear the craning of necks as men fought for a better view.

She had the best view of all, and jumped at the sight. The boy’s eyes had opened, but just the whites – his pupils had rolled round inside his head – and his tongue lolled from his gaping mo

uth.

Haralt tittered at Astrid’s obvious discomfort.

‘He’s in a trance,’ said her mother, ignoring her second son. She raised her voice. It was high, lofty, commanding. ‘What do you see, boy?’

‘I see you, Thyre, adornment of the Dane-mark.’

Astrid was not the only one to start at this; the boy spoke like two rocks rending, and it was awful to see, for his lips never moved.

‘And I see you, King Gorm, Knut, Haralt, Astrid – all those in this hall, and all their womenfolk and children. But I do not see the hall itself: we walk, a thousand strong, down a road between high mountains.’

‘A vision,’ someone muttered.

‘Hush,’ came a reply.

The boy never paused. ‘Now there is a boiling river ahead. It spits and froths, coming ever closer. Here the road forks; I know not which to choose.’

So terrible was his manner of speech, that all hung on his words.

‘The left leads to a man, who stands alone. His skin is dark; his robes are thin and white; he wears a crown of thorns upon his head. He says we have to walk on the water. The right hand path ends with a ferryman; his raft is broad enough to take us all. This man is old, and leans upon his staff – his face is hid beneath a broad-brimmed hat.

‘So now I move towards him – but some danger blots the sun! A thing with wings descends upon the man, who raises up his staff to fend it off. The creature beats about him, tries to strike … I cannot see … the sun is going … I cannot reach him …’

The Yelling Stones

The Yelling Stones